San Francisco’s Downtown Plan turned 30 this year. The plan came about in the midst of the 1980s “Planning Wars,” when battles over density, building height, and office uses were fought in City Hall and the ballot box.

The Downtown Plan attempted two reconcile two contending visions of the city – that of postwar Modernism, which had transformed much of San Francisco with steel and glass high rises, freeways, parking structures, and large-scale urban renewal projects which bulldozed entire neighborhoods, and that of traditional urbanism, based on human-scaled buildings, walkability, small blocks, and a fine-grained mix of land uses.

When the plan was adopted, it won considerable praise for its integrated approach. Architecture theorist and critic Charles Jencks wrote:

It’s virtually the most comprehensive urban development plan ever conceived in the United States. Fundamentally it entails that office development be cut down in size and shape to smaller, thinner towers that prevailed in the International Style blocks of the 1960s, and that speculators will put aside part of their investment to pay for public open space, works of art and public transport . . . Older buildings and districts are to be preserved, mixed use incorporated, housing for secretaries, janitors, and executives provided (those who work in the new office space), one percent of the budget made over to public art works, money put aside for child-care funds and five dollars per square foot of new construction put towards the cost of public transport. In effect Dean Macris [then Planning Director] has managed to pass legation that favors the public over the private realm, and communal open space over the automobile. In America this reversal of prevailing values is unique, at least on such a scale.”

Some of the provisions of the plan praised by Jencks and others were part of Proposition M, a voter-approved measure that passed in November 1986. The adoption of the Downtown Plan, and the passage of Proposition M the following year, have provided the planning framework for Downtown’s growth over the subsequent decades. The Transit Center District Plan, which was approved in 2012, built on the guiding principles of the Downtown Plan – it permits taller towers, but kept the requirements for spacing and tapering to permit sunlight and reduce ground-level winds, further reduced allowable office parking to reduce auto congestion and encourage sustainable transportation, and strengthened the requirements for streetscape improvements and transit funding from new development.

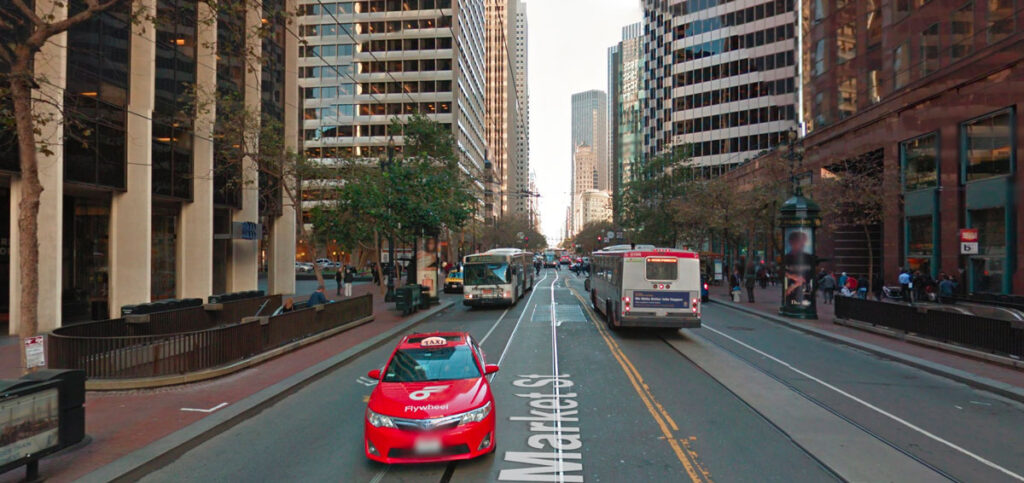

The Downtown Plan built on regional transit investments made in the 1970s, including BART and the Muni Metro underground, and on San Francisco’s Transit First Policy, first adopted in 1973, the year that BART opened in Downtown San Francisco. The plan clustered new office development along Market Street, and set maximum amounts of parking for office and other uses. About 60% of Downtown workers take transit, walk, or bicycle to work, making Downtown San Francisco the most transit-oriented jobs center in the Bay Area, and fourth in the US behind New York, Washington, and Boston.

However, recent years have also seen a resurgence of what John Parman calls the “sorry tradition of case-by-case rezoning in San Francisco.” An increasing number of projects are being brought forward that flout the Downtown Plan’s policies and standards – the excess parking awarded to the Market Street Place shopping mall, the bulky towers proposed by the 5M project, and Trinity Plaza’s vast gray slabs rather than the tapered towers and active street frontage called for in the Downtown Plan. As former Planning Director Allan Jacobs recently observed, “More and more things are being done by discretion rather than by what the zoning laws say. That is always a mistake because when you do that, the party with the most power always wins. And that party is never the city planner.” Five years ago, the Chronicle’s architecture writer John King called for a revived and refreshed Downtown Plan, and noted the cost of not having one: “As long as downtown is up for grabs, in effect, count on the process to grow more strident and cynical.”

The best way forward for Downtown is in accordance with the rule of law and guided by a Downtown Plan that is comprehensive and strategic yet provides necessary flexibility, rather than a further lapse into the corrupting habit of planning-by-exception. Fortunately we have a strong Downtown Plan to build on, one whose key strategies – a compact Downtown oriented to walking and public transit, a proper balance between public and private, well-designed and dignified streets and public open spaces, housing for residents of diverse incomes – are as timely now as they were three decades ago. In some key areas the Downtown Plan has fallen short of its goals. In some cases, it’s because actual planning and zoning controls are out of step with the Downtown Plan’s policies. In others, the Planning Department, other agencies, and/or elected officials aren’t committed to the policies and implementing actions necessary to realize them.

Central Business District or Central Social District?

Post-World War 2 planning placed great faith in functional zoning – physically separating activities like housing, offices, shops, and industry into distinct zones, to rationalize and simplify the city and to prevent potential conflicts between uses. San Francisco had grown and developed for nearly a century without zoning, and uses were mixed together in that perplexed and dismayed postwar planners. Early zoning schemes relied on a simple three-part zoning scheme, which established R (residential) districts for housing, C (commercial) districts for offices and shops, and M (manufacturing) districts for industry. It was presumed that nonconforming uses – uses that didn’t fit the new zoning – would be phased out over time, and order imposed on the chaos of the city. Downtown became the C-3 (downtown commercial) district, dedicated primarily to offices, and secondarily to retail.

The Downtown Plan retained a focus on Downtown as the City’s, and the Bay Area’s, central business district, but acknowledged and encouraged complementary uses, like retail, hotels, and support services.

The Downtown Plan encouraged ground-floor retail uses by providing a density bonus incentive in the Financial District, and requiring ground-floor retail in the Downtown Retail (C-3-R) sub-area around Union Square. Union Square remains the region’s destination retail center, but retail uses elsewhere in Downtown struggle. Union Square is an established shopping district that is enlivened by its diverse mix of uses – offices and retail, but also hotels, housing, convention center, theaters, and museums. The less diverse parts of downtown, like the Financial District, have retail uses oriented to office workers, but little evening or weekend activity. A more diverse Downtown – more residents, more arts and culture – could support more shops and restaurants. Many Downtown streets are too dominated by auto traffic and poorly-designed buildings to support healthy retail districts, as we discuss below.

Downtown is also home to arts and culture, including the theater district west of Union Square, the museums and theater in Yerba Buena, and galleries, performance spaces, and spaces for artists. Mid-Market, which once was home to many theaters and cinemas, now supports a handful. It has, over the years, been proposed as an arts and theater district. One historic theater, the Strand, was recently restored and reopened by ACT, but another, the St. Francis, was demolished for a shopping mall. Downtown’s zoning provides few incentives for art spaces and doesn’t protect them from conversion, so many art spaces, galleries, and arts and culture nonprofits have been priced out of Downtown or are under threat of displacement.

Affordable Housing

During the urban renewal decades of the 1950s and 60s, San Francisco’s Redevelopment Agency demolished hundreds of affordable apartments and residential hotels in Yerba Buena and Golden Gateway. By the mid-70s Redevelopment had reversed course, and redevelopment projects of the 80s and 90s replaced and rehabilitated housing in Yerba Buena and around 6th Street. The Downtown Plan aimed to preserve existing housing by placing strict limits on residential demolition and conversion.

However the plan didn’t contemplate that much new housing would be built Downtown; instead, it called for protecting existing affordable housing in the adjacent Chinatown and Tenderloin neighborhoods, and building new housing in South of Market, Rincon Hill, and the Van Ness corridor. Supervisor Carole Ruth Silver proposed a middle-income housing zone in Mid-Market in the mid-1980s. The notion was revived two decades later in the Mid-Market Redevelopment plan, which then fizzled. High-rise projects have been built in Downtown, but most are expensive towers without on-site affordable units The Market and Octavia Plan rezoned the area around Van Ness and Market for high rise residential, but little of that will be permanently affordable; few developments meet their affordable housing obligations on-site, or in Downtown. Housing in the Transbay Redevelopment Area, around the new Transbay Transit Center, will be 35% affordable by state law. Affordable housing in and around Downtown remains a compelling need.

Livable City worked with Supervisor Chiu to remove the Conditional Use requirement for dense housing downtown, which added risk and cost to both affordable and market-rate housing projects. We proposed a floor-area-ratio exception for affordable housing as an incentive to build affordable units downtown, which was partially enacted this year. More incentives, as well as direct funding for housing through impact fees and the proposed housing bond, could help create more affordable housing downtown. The City could build affordable housing on the site of some of Downtown’s city-owned parking lots and garages, like the Yerba Buena Garage on 3rd Street.

Reducing the amount of off-street parking in Downtown housing decreases the cost to built and to rent housing, and decreases automobile congestion by encouraging residents to use Downtown’s sustainable transportation options. Livable City helped eliminate Downtown’s minimum parking requirements for housing in 2006, and where parking is provided, the cost of parking must now be unbundled from sale or lease costs. Within the last five years, we helped eliminate minimum parking requirements in the neighborhoods adjacent to Downtown – the Tenderloin, Chinatown, and SoMa.

Sustainable Transportation

Downtown has long been the hub of the region’s public transportation system, and was revitalized by in investments in rail transit. In 1962, the voters approved a bond to build the three-county BART system, and the Muni Metro subway. BART service opened in 1973, and the Muni metro opened in the late 1970s. Today both rail systems face capacity constraints and overcrowding, and need major reinvestment in aging infrastructure.

The 1973 Transit First policy included an action plan for prioritizing transit on city streets. Expanding transit priority – dedicated lanes, bus bulbouts, traffic signal priority, etc. – on the bus and light rail lines serving Downtown are essential to improving the speed, reliability, and accessibility of surface transit, and are the focus of SFMTA’s Transit Effectiveness Project and Muni Forward initiatives.

After the flurry of activity in the 70s, little changed in the subsequent three decades. However recent moves to establish transit priority on Market Street have been modest but effective. Better Market Street could restrict private cars altogether.

The Caltrain line has been in operation for over 150 years, and is the region’s oldest passenger rail service. Extending Caltrain Downtown has been talked about for over a century, and by the end of the decade we will see two significant strides towards that vision. The Transbay Transit Center’s first phase, due to open in 2017, will reopen a needed transbay bus terminal and construct the shell of an underground rail station, and electrification of the Caltrain line will begin in the next few years. The second phase of Transbay, extending electrified Caltrain service to downtown, is designed but not fully funded, and completing this regional link ought to be a top priority for the City.

Downtown streets and public spaces

The Downtown Plan prioritized public transit, walking, and cycling, but Downtown’s streets, which had been reengineered in the auto-oriented 50s and 60s, still prioritize the automobile. As a result, surface transit often moves slowly, and conditions for pedestrians and cyclists can be unacceptably dangerous. Adjacent neighborhoods, especially SoMa and the Tenderloin, sacrificed their livability to move downtown traffic.

The Downtown Plan called for a Downtown Streetscape Plan, which was adopted in 1995. The Downtown Streetscape Plan included an action plan for its first year, but the City quickly lost interest, and Downtown streets have seen little improvement since.

Past decades saw an uptick in defensive urbanism, where activities like shopping retreat from city streets into private spaces, mirroring San Francisco’s rising income disparity. One symptom is the increase in enclosed shopping malls in the downtown since the Downtown Plan was adopted. As Enrique Peñalosa observes, “When shopping malls replace public space it is the result of a sick city with poorly performing public spaces. People are not stupid, they go to the shopping malls because it offers a pedestrian environment they can’t find anywhere else.”

Cities around the world, including New York, Paris, London, Copenhagen, are making increasingly bold moves to decongest their downtowns and reclaim downtown streets from traffic. San Francisco saw little action to reclaim downtown streets after the 1970s, but there has been a flurry of activity in the last decade, mostly tactical and tentative, aimed at moving transit on city streets, improving walking and cycling, and reclaiming streets as public spaces.

The biggest effort has been along Market Street, Downtown’s primary street for transit, walking, and cycling. In the past several years, SFMTA has added transit-only lanes, bicycle lanes, and curb extensions to the street to improve the street for transit, walking, and cycling, and required limited auto access to reduce traffic on Market. These modest changes have been effective, and we await the Better Market Street project, which may finally eliminate automobile congestion on Market Street and improve safety and mobility for pedestrians, cyclists, and transit riders. SFMTA recently proposed removing auto traffic from two blocks of Powell Street in Union Square.

Market Street’s main public spaces – The cluster of spaces at the foot of Market Street including Justin Herman Plaza, Hallidie Plaza at Powell and Market, and Civic Center Plaza – have not been very successful, but the past decade’s efforts to activate these spaces with activities like farmers markets have brought life to them.

Some Downtown alleyways have been reclaimed as public open spaces. Maiden Lane, Belden Place, Leidesdorff Street, and Claude Lane have become popular outdoor eating places, and more recently, Mint Plaza and Annie Alley Plaza have become fully pedestrianized.

The Downtown Plan also required POPOS – privately-owned public open spaces – from new developments in the Downtown. Some POPOS have proved popular and genuinely public, while others, by virtue of their design, location, or management, are de facto private spaces.

Some of Downtown’s most successful public open spaces are in Yerba Buena Gardens, an interconnected set of gardens and children’s attractions built by the Redevelopment Agency. The Gardens have their own management and public funding sources, and discussions of how to fund and govern the gardens after Redevelopment is dissolved are currently underway.

The building, planning and management of Downtown’s streets and public spaces has been piecemeal. Downtown would benefit enormously from a revival of the Downtown Streetscape Plan, and a strategy for implementing necessary changes.

Please join us at Tomorrow Transit: The Future of the Downtown Plan on October 15 with downtown movers, shakers, and decisionmakers as we develop the action plan for the neighborhood. We will explore the future of this urban landscape, how we move people from point A to point B, and its increasing role as a central social district.