We are in the midst of a growing global ecological crisis. Heat waves, droughts, floods, highly destructive storms, and rising seas caused or worsened by global heating increasingly dominate the news. Global emissions of greenhouse gases are still increasing each year. More experts are saying we have very little time to start reducing emissions before the damage we’re doing is irreversible and threatens human survival.

And climate isn’t the only existential crisis. There is an unprecedented and accelerating loss of biodiversity and its ecosystem services – “the many and varied benefits that humans freely gain from the natural environment and from properly-functioning ecosystems”. Earlier this year, the UN warned that this loss is threatening one million species with extinction, and endangering human prospects as well.

Pollinators are in decline worldwide, threatening the food supply. An estimated seven million people per year die prematurely from air pollution. After improving for many years, air quality in the US is once again worsening. More cities and regions are running out of drinkable water. These global crises are linked, and mutually reinforcing.

Recently, San Francisco has taken steps to address some of the pressing global environmental challenges. The Board of Supervisors declared a Climate Emergency, directing City agencies to take action. Last year, the Board adopted a biodiversity policy. CleanPowerSF offers 100% renewable electricity to thousands of San Francisco households and businesses.

San Francisco has stronger policies, and some demonstrable successes – from recycling to habitat restoration. However, the city’s progress towards sustainability remains slow, uneven, and poorly understood. This article and the ones that follow will lay out a path to a sustainable San Francisco. Our sustainable path must also increase the City’s resilience – our ability to withstand the upcoming environmental shocks – be equitable, transparent, and democratic, and further San Franciscans’ health and happiness.

Defining sustainability

The most succinct definition of sustainability is by Donella Meadows. It first appeared in the 1987 report of the International Commission on Environment and Development: “to meet the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs.”

Meadows cited Herman Daly to describe what that means in physical terms:

- Renewable resources [soils, forests, fisheries, fresh water, etc.] shall not be used faster than they can regenerate.

- Pollution and wastes shall not be put into the environment faster than the environment can recycle them or render them harmless.

- Nonrenewable resources shall not be used faster than renewable substitutes (used sustainably) can be developed.

Meadows also stressed that ecological sustainability was only half of sustainable development; the other essential element is meeting human needs. Sustainable development must “keep the welfare of both humans and the environment in focus at the same time, and . . . insist on both.” For Meadows, the social and ethical dimensions were integral, and the conditions of sustainability “have to be met through processes that are democratic and equitable enough that people will stand for them.”

The Path to Sustainability

In describing sustainable development, Meadows observed that “there’s not a nation, a company, a city, a farm, or a household on earth that is sustainable.”

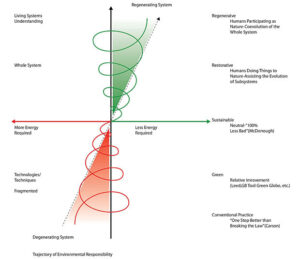

So if there is no alternative to sustainability that doesn’t lead to planetary disaster, then how do we get there? As Bill Reed, Daniel Christian Wahl and others explain, progress towards sustainability typically goes through three stages.

After moving from business as usual, the next step is through “green approaches”, which minimize environmental damage in one or more areas, to sustainability, and even beyond.

Green approaches can be considered “steps in the right direction” and may include everything from compostable single-use products to the process of recycling itself. These approaches are less bad, by a little or a lot, than business as usual.

Sustainable is, in the words of William McDonough, “100% less bad”. Various tools and methods for moving towards sustainability and measuring progress have been developed in recent years; we’ll explore them further in a future post.

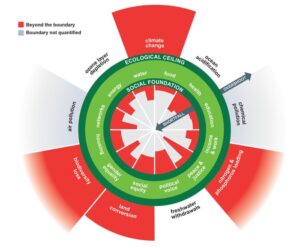

For the last two decades, the Stockholm Resilience Centre have been working to define planetary boundaries. Planetary boundaries are the limits to which humans can alter the critical life systems on the planet without endangering the integrity of those systems, and our survival. Staying within these limits defines the ‘safe operating space for humanity’.

Economist Kate Raworth combines the insights of ecologists like Meadows and Daly and the planetary boundaries into Donut Economics. The twelve dimensions of Raworth’s social foundation are based on the UN’s 2015 Sustainable Development Goals.

Like Meadows, donut economics focuses on the welfare of both Like Meadows, donut economics focuses on the welfare of both people and the environment. Providing the social foundation for the one billion humans whose most essential needs are currently unmet is, according to Raworth, not a big challenge to sustainability.

13% of people currently don’t have enough food to eat, but their needs could be met with around 3% of today’s global food supply – about one-tenth of the food that is wasted or thrown away each year. Basic electricity could be provided to the 19% of people without electricity access with just a 1% increase in global CO2 emissions. It would take less than 0.2% of global income to lift the 19% of people who earn less than $1.25 a day out of extreme poverty.

The greater challenge is sustaining the resource-intensive lifestyles of the most affluent – the 11% of people, including most Americans, who produce about half the world’s carbon emissions.

Like the planetary boundaries, sustaining the social foundation – access to energy, water, food, education, health and health care, income and work, social networks, peace and justice, a political voice, social equity, and gender equality – requires governments to devise better measures and specific strategies. We’ll return to the importance of those measures and strategies in a later post.

The promise and pitfalls of Green

While true sustainability is still relatively rare, we are surrounded by products, activities, and processes labeled “green”. Many – like LEED ratings for green buildings – are an improvement, big or small, over business as usual. We can also make environmental progress by changing business as usual; California’s building energy efficiency standards, known as Title 24, were adopted in 1978 and are updated every few years.

Racheting up the minimum standards for new construction and renovations have helped reduce business and household use of energy and water. The state estimates that homes built to the 2019 standards will use 7% less energy than those built to the 2015 standard, and 53% less when required rooftop solar electrical generation is factored in.

Green approaches also have pitfalls. One of them is greenwashing – deceptively promoting products, activities, or policies as environmentally-friendly when they actually increase harm. A recent example is the growing crisis around plastics recycling. Fossil fuels – oil, natural gas, and coal – account for 99% of what goes into making plastic. As the use of plastics, particularly single-use plastics, has increased, governments and the plastics industry encouraged plastics recycling.

Recycling plastics seems far less damaging than incinerating plastics or burying them in a landfill, and cities like San Francisco prided themselves on the tonnage of plastics diverted from landfills, and even counted landfill diversion towards their greenhouse gas reduction goals. The problem with plastics recycling is that most plastic can’t actually be recycled; much of what is called plastics recycling is actually downcycling.

Downcycled materials, like second-generation plastics, are typically of lower quality and functionality than the original material, so a plastic water bottle might end up in a speed bump or a park bench but is unlikely to end up as a new water bottle. Only 9% of plastics worldwide are collected for recycling, and the majority of plastics collected for recycling won’t be recycled, or even downcycled. China’s refusal to accept the US’ plastic trash has caused plastics to pile up in recycling centers; most if it will likely be burned, end up in landfills, be illegally dumped, or get shipped to poor countries where much of it will still be burned or dumped.

Tiny bits of plastic, known as microplastics, are an increasing danger to human health, since they can find their way into our bodies, and even our bloodstream. Recycling plastics – for example, turning milk bottles into plastic fabric – can actually increase exposure microplastics pollution. Plastics recycling has turned out to be more of a dead end than a path to sustainability.

One thing plastics recycling did do is make people feel better about consuming ever-increasing amounts of plastic. Plastic production continues to increase exponentially; over half the plastics produced in human history have been produced since 2000.

What if we had been unwilling to accept the dubious ‘less bad’ arguments made for plastics recycling, and insisted on a more sustainable path? A better solution would phase out the use of fossil-fuel based, non-compostable or non-recyclable plastics, and reduce use of throwaway plastics. Countries around the world have done this for single-use plastic bags, as has San Francisco by banning plastic water bottle sales on city property.

There are other examples of how ‘less bad’ approaches can actually move us further from sustainability; we’ll explore those pitfalls, and how get back on a sustainable path, in future posts.