It’s hard to imagine a city without retail – shops, retail services, cafes, restaurants, and bars. Retail contributes to city vitality, character, and livability, as well as the city’s economy.

Retail businesses provide thousands of jobs. A robust locally-owned retail sector expands and diversifies economic opportunities for residents. Local ownership also provides an economic multiplier effect – local owners, including worker-owners, spend and invest more of what they earn in the local economy, while the profits of national and multinational chains typically leave the local economy.

Local-serving retail businesses contribute to walkability. Residents and workers daily needs are within convenient walking distance, and ‘eyes on the street’ enhance street safety and make walking interesting.

Since 70% of trips are non-work trips, walkable retail can reduce the need for auto trips, especially when located along transit lines and around transit stations.

Retail businesses foster community and sociability. Eating and drinking especially provide vital ‘third spaces’ – beyond work and home – that make city life more social, people more connected, and even foster innovation. Independent businesses like bookstores and hardware stores offer not only goods for purchase, but also knowledge and expert advice.

Many small businesses, especially those with worker-owners, become hubs for the community to stop in and chat about the neighborhood. Long-standing relationships between community members, worker-owners, staff and other customers make up an important part of the social fabric. Independent retailers provide color, character and a unique, neighborhood-specific feel to a district.

But retail is at a crossroads. The rise of internet retailers and the delivery economy threatens many local retailers, and San Francisco, like other American cities, finds rows of empty storefronts on even its most popular corridors.

The City’s skyrocketing rents are another formidable threat, as is the consolidation of both retail business and property ownership into fewer and fewer hands, as banks, real estate trusts and development firms buy up retail spaces once operated by small landlords.

“There’s too much retail,” is a common refrain, including from many decision-makers. “We ought to accept the takeover of retail and brick-and-mortar stores by big internet retailers.”

We argue that the death of retail is neither inevitable, nor desirable. The internet and other technological, economic, and social forces will transform retail enormously in years to come, but the vast contributions retail makes to city livability is something we can, and should, preserve. Getting retail right is a powerful tool for advancing neighborhood livability, sustainability, equity, and health.

City policies clearly support neighborhood-serving retail. The first of the eight Priority Policies in San Francisco’s Planning Code is that “existing neighborhood-serving retail uses be preserved and enhanced and future opportunities for resident employment in and ownership of such businesses enhanced”.

However the City’s regulations and practices don’t always pull in the same direction as its policies. Livable City has long championed programs and policies that support neighborhood-serving retail, as well as transit-oriented regional retail and visitor-oriented retail.

Here we present our comprehensive program for retail in San Francisco, supporting a more sustainable, equitable, and livable City. Part one addresses buildings and zoning. Part two will address streets, transportation, and citywide planning, and includes an action plan.

The paradox of high rents and high vacancies

In the past few years, San Francisco has seen huge increases in both commercial rents and the number of vacant storefronts. Every day, the papers are filled with stories of small businesses forced out by cataclysmic rent increases, or landlords refusing to renew leases. Many spaces in newly-built buildings have never been leased, with huge, gleaming empty storefronts sitting below pricey condo, apartment, or office buildings. Office and housing developers tout proximity to San Francisco’s commercial districts to market their properties, but many of those same developments have left their retail spaces untenanted.

Rising rents make the ‘we have built too much retail’ arguments questionable. If there’s too much retail, why are retail rents still increasing?

The answers are complex. In San Francisco’s overheated property market, buildings can make more money as investments than they do in rents. Property owners may be holding out for chain stores that will offer steep rents, long leases, and financial guarantees that many local businesses can’t afford. The way commercial property is financed can encourage owners to keep properties vacant, rather than lower rents to what potential tenants can afford.

Vacant stores impose a burden on communities and on local government. They sap community vitality, reduce sidewalk safety, and attract graffiti, litter, dumping, and arson. It’s in the general neighborhood interest – and in the interest of property owners – to keep retail spaces occupied, but landlords often try to maximize their individual interests above the common good.

Strengthening financial disincentives for leaving retail spaces vacant will nudge owners to either lease the spaces, and make necessary improvements, or sell to someone who will. San Francisco passed a fee on long-term vacant commercial property, but loopholes in the law make it easy to avoid the fee. Recently some cities have imposed a special tax on vacant property. Such a tax in San Francisco would require voter approval. State law outlaws any form of commercial rent control.

The City can also expand its assistance to small businesses by securing long-term leases or purchasing their buildings, and for brokering vacant properties to potential tenants. In the past, these programs were often funded through the City’s Redevelopment Agency, and many were dropped when the State dissolved redevelopment agencies in 2011 during the nationwide recession. Reviving and expanding the more successful of these programs would be a smart investment.

Creating the right mix of uses

Retail works best when mixed with other uses and activities in complete and diverse neighborhoods. Residential districts are enhanced by walking distance to retail, including corner stores and neighborhood commercial streets. Retail also enhances office districts. Walkable retail benefits from nearby concentrations of residents, workers, and visitors.

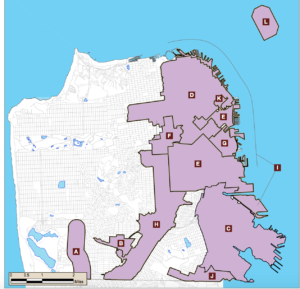

The City’s Planning Code regulates which uses are permitted in each of the City’s 113 zoning districts. The majority of the City’s zoning districts permit retail, at least on the ground floor.

Zoning controls can enhance retail vitality by permitting complementary uses, and keeping in check other uses – chiefly office spaces – which can displace desirable retail.

The City’s Neighborhood Commercial and Residential-Commercial zoning districts prohibit office uses entirely. However, in Downtown and SoMa, offices are generally permitted on the ground floor, and booming demand for office space has displaced retail from some street-facing ground floor spaces. As these neighborhoods grow denser and add more residents, preserving and fostering neighborhood-serving retail becomes increasingly important, and the zoning in Downtown and SoMa must treat retail as more than an afterthought.

Access to healthy food is essential for neighborhood livability. Many neighborhoods are ‘food deserts’, lacking nearby places to buy healthy and affordable groceries. The City’s Healthy Retail SF program is working with owners of existing stores to encourage them to stock and market healthy foods, and provides technical and financial assistance to store owners and residents.

The City doesn’t have a strategy for attracting new grocery stores to neighborhood food deserts, or to expand alternatives, like farmer’s markets and community farms and gardens, which increase access to healthy and affordable food.

Formula retail controls impose additional restrictions on where retail chains can open, and are meant to reduce the competition retail chains impose on small and locally-owned businesses. The first Formula Retail controls were established in 2004 in a handful of Neighborhood Commercial Districts.

In 2007, the voters extended formula retail controls to all of the City’s Neighborhood Commercial districts, and they were extended to Residential and Residential-Commercial districts in 2014. Formula Retail controls generally require conditional use authorization – a public hearing and approval by the Planning Commission – before a formula retail business can be established.

When communities have input, they tend to strike a balance between local businesses and formula retail ones that fits their neighborhood’s needs. A 2014 study commissioned by the Planning Department concluded that “the community has generally supported conditional use applications for formula retail that fills long-standing needs, but organized to oppose a formula retail use that competed with existing small businesses.”

The zoning in many commercial districts imposes limitations on certain types of retail uses, particularly restaurants, bars, liquor stores, and entertainment venues. These restrictions may involve quotas – an upper limit on businesses of a certain type, or conditional use authorization, which requires an application process and a public hearing at the Planning Commission. Restrictions like these either originated decades ago when zoning districts were first established, or were created in response to a perceived overabundance of these types of retail uses at some point in the past, or in response to certain neighbors’ disapproval of certain types of businesses.

Once the restrictions are in place, there is no established procedure to review and evaluate them, so they tend to stick around. These limitations can impose a burden on local businesses. Conditional use authorization can take up to a year, and approval is at the discretion of the Planning Commission, so a small business may need to pay rent for several months before they can open, without any assurance that they will get approval.

Approval for a use is granted to a particular space, but not to a particular business, which gives landlords an advantage in lease negotiations. When a business’ lease expires, they may not have the option of leasing another space in the same neighborhood; they must either pay whatever the landlord demands, or move out of the neighborhood or close up shop entirely. San Francisco should thoroughly and periodically review, and where advisable relax, controls on uses which have outlived their usefulness, and which are contributing to the demise of neighborhood-serving businesses.

The City also employs conditional use and prohibition of uses to manage potential conflicts between certain types of businesses and neighbors. Mixed uses, especially mixing residences with other uses, does create the potential for conflict, even if the non-residential uses are otherwise neighborhood-serving. To foster livability and diversity, impacts like noise, odors, queueing, and vehicle loading must be addressed.

Livable City worked with the Planning Department to create, clarify, and expand standard operating conditions which apply to specific uses, and address their impacts. These operating conditions require businesses to manage impacts such as noise, odors, trash, and so on, and businesses can be held accountable for violation. Operating conditions, also known as performance zoning, is an effective way of making mixed use work, by setting clear parameters for successful coexistence in close proximity. As we improve our performance zoning, we can consider relaxing restrictions on certain types of neighborhood-serving uses.

Combining production and retail – food, beverages, clothing, personal and household goods, etc. – can make both more viable. San Francisco has higher rents and higher labor costs than many nearby communities, but many production businesses find that combining retail with production – bakery cafes, coffee roasters, factory stores, etc. – offsets the higher cost of doing business here. A healthy production, distribution, and repair sector creates a more diverse job base for the City, and provides esssential goods and services to other City businesses. The City’s industrial zoning districts permit accessory retail, but the city’s commercial and mixed-use zones restrict on production accessory to retail. In 2011, the City relaxed limits on production accessory to retail in the City’s Neighborhood Commercial Districts, but the Commercial, Residential-Commercial, and Mixed-Use zoning districts still maintain the old restrictions.

Non-retail uses which are currently restricted – namely arts activities and nonprofits – should be permitted in Neighborhood Commercial and Residential-Commercial districts. These serve local residents, and arts spaces especially attract visitors, and serve as the cornerstone of arts-centered economic revitalization in corridors that need a boost. Arts and nonprofits generally won’t out-compete retail on rents, but are increasingly getting displaced by office uses in districts where both are permitted.

Livable City’s arts strategy has more about how to make San Francisco friendlier to artists and arts spaces, and engage the arts in enhancing neighborhood vitality and character.

Getting zoning right, so that the right uses are permitted, incompatible uses are restricted, and all uses make good neighbors, can do a lot to allow neighborhood-serving retail businesses and retail districts to thrive.

The City can, and should, take a more proactive role in assisting small and local businesses. The Legacy Business Program, which helps longstanding local businesses secure long-term leases, can be expanded. Community-based business incubators like La Cocina are helping expand economic opportunity by assisting San Franciscans, especially women and people of color, grow and expand food-based businesses.

The City can expand facade improvement programs like SF Shines, which provide grants and loans for signage, awnings, windows, and other facade improvements. Facade improvements benefit both individual businesses and the neighborhood as a whole by enhancing street life and walkability. The City can again offer its PACE program to small businesses, providing financing for energy-conserving equipment and building retrofits.

Fostering diverse and high-quality retail spaces

High-quality retail spaces – level with and facing onto the sidewalk, transparent to the street, and with tall ceilings – make better retail districts. Older commercial buildings typically have these features, and contribute to the walkability, vitality, and character of commercial our districts.

Livable City helped revise the City’s zoning controls to ensure that buildings mostly have active uses, which may be residential or commercial, facing towards the street, and that ground-floor commercial spaces in new buildings include transparent windows and doors. Garage doors are limited in width, and may be oriented away from the main commercial street. Adoption of these standards has improved ground-level building design, although the Planning Department’s enforcement of its own standards is very uneven.

We also worked to amend height controls in various zoning districts of the city, so that developers can create taller ground-floor ceilings or raise dwellings a few steps from the sidewalk without having to lose an upper floor. The Planning Department’s formula retail study found that buildings with ‘design challenges’ – including ugly buildings, buildings with small windows or low ceilings, and buildings that are awkwardly connected to the sidewalk – often prove difficult to lease. The vacant buildings create gaps in street activity which reduce the walkability and vitality of the commercial corridor. With sufficient investment, design-challenged buildings can be improved, but it’s better to build them right in the first place.

Off-street parking and garage entrances can compromise building design. The imposition of citywide parking requirements after 1955 meant that that all new buildings had to provide parking off-street. Garage doors proliferated in commercial and residential districts, and storefronts and on-street parking were displaced to make way for them.

Livable City has worked to relax or eliminate minimum parking requirements, and permit the conversion of garages to storefronts or living space. These conversions have helped create new retail spaces for neighborhood-serving businesses, and enhanced the character and walkability of commercial districts by replacing garage doors and driveway cuts with active storefronts and uninterrupted sidewalks.

The size of retail spaces is also a factor in sustaining diverse and healthy retail districts. Independent businesses often prefer smaller and shallower retail spaces, and retail districts which provide a mix of spaces that includes smaller retail spaces have proved more diverse and resilient. Developers of new mixed-use tend to favor large retail spaces; fewer, larger spaces are cheaper to build, simpler to landlord, and are more attractive to national chains.

However larger commercial spaces generally stay vacant longer, especially as the national retail chains they cater to continue to merge and downsize.

Neighborhood Commercial Districts generally have a maximum size limit for commercial uses, above which Conditional Use is required, and a few have prohibited the merger of ground-floor commercial spaces to create larger spaces. Some over-large retail spaces be able to be divided into smaller stores, but in many cases building design or layout may make such retrofits impractical. As with ground-floor transparency and ceiling heights, establishing a mix of retail space sizes as buildings are designed and approval stage is much easier than trying to divide them later.

Continue to Part 2

The San Francisco Foundation

The San Francisco Foundation Barbara Garcia, Director of San Francisco’s Department of Public Health

Barbara Garcia, Director of San Francisco’s Department of Public Health Mission Economic Development Agency (MEDA)

Mission Economic Development Agency (MEDA)  Chema Hernández Gil

Chema Hernández Gil Homeless Youth Alliance

Homeless Youth Alliance

SILVER

SILVER

California’s clean energy mandates contributed to the decline in coal use in California, and since California is the largest electricity consumer in the western US, in neighboring states as well. In 2017, California’s growing greenhouse gas emissions from transportation surpassed emissions from electricity generation for the first time, making transportation – mostly automobiles – the state’s biggest single contributor to climate change. The state legislature approved a gasoline tax increase to reinvest in California’s roads, highways, transit, cycling, and walking, which went into effect on November 1. On December 14, the California Air Resources Board adopted its 2030 plan to reduce California’s greenhouse gas emissions 40% below 1990 levels within the next 13 years. The plan relies on expanding renewable power sources and electric vehicles, but also walkable and bikeable communities, expanding and electrifying public transit and intercity rail, focusing housing and jobs near transit, and capturing carbon by restoring the states’ soils, forests, wetlands, and grasslands.

California’s clean energy mandates contributed to the decline in coal use in California, and since California is the largest electricity consumer in the western US, in neighboring states as well. In 2017, California’s growing greenhouse gas emissions from transportation surpassed emissions from electricity generation for the first time, making transportation – mostly automobiles – the state’s biggest single contributor to climate change. The state legislature approved a gasoline tax increase to reinvest in California’s roads, highways, transit, cycling, and walking, which went into effect on November 1. On December 14, the California Air Resources Board adopted its 2030 plan to reduce California’s greenhouse gas emissions 40% below 1990 levels within the next 13 years. The plan relies on expanding renewable power sources and electric vehicles, but also walkable and bikeable communities, expanding and electrifying public transit and intercity rail, focusing housing and jobs near transit, and capturing carbon by restoring the states’ soils, forests, wetlands, and grasslands.